Tea is a popular beverage enjoyed by people all around the world. But where did it come from? Let’s delve into the history of tea and see how it was evolved over the centuries.

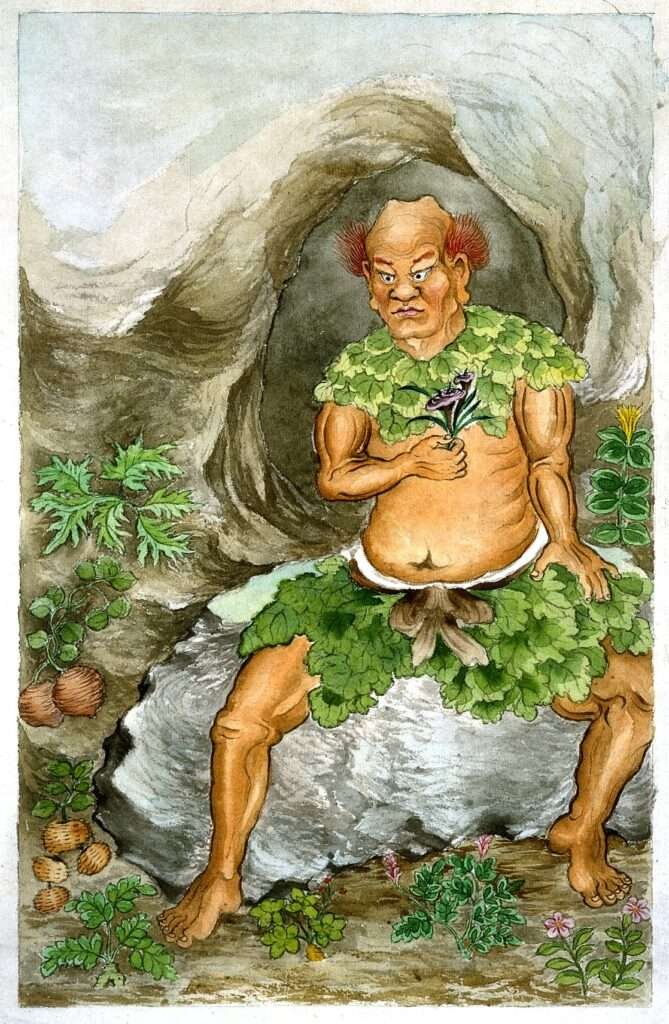

The origins of tea can be traced back to ancient China, where it was first used as a medicinal drink. Once upon a time, a legendary farmer named Shen Nong got poisoned a lot while looking for food in the forest. But one day, he accidentally ate a leaf that saved him. This leaf turned out to be tea!

Shen Nong was a skilled healer and is credit with introducing a number of important herbs and plant to China, including tea. Tea has been around for a really long time, like 6,000 years. Back then, people in China didn’t drink tea like we do now. They ate it or cooked it with their food. The early Chinese used tea for its medical properties, believing it could cure a wide range of ailments. About 1,500 years ago, someone figured out that if you mix tea with hot water, it tastes really good. They made tea into small cakes or powder called “Mou Cha” or “Matcha.” People loved Matcha so much that it became a big part of Chinese culture. And that’s how tea went from being food to being a drink we all enjoy today!

In the 8th century, the famous Chinese monk Lu Yu wrote “The Classic of Tea” a treatise on the art of tea cultivation and preparation. This book became a key text in the development of the industry in China and helped to spread the popularity of tea throughout the country. Tea also played a role in the development of Zen Buddhism in Japan.

Tea became a cherished subject in literature and poetry, adored by emperors and a muse for artists who crafted intricate designs in the foam, reminiscent of modern espresso art. In the 9th century, during the Tang Dynasty, a Japanese monk introduced the first tea plant to Japan, sparking the development of unique tea rituals and the iconic Japanese tea ceremony. By the 14th century, during the Ming Dynasty, the Chinese emperor shifted from pressed tea cakes to loose leaf tea as the standard. China maintained control over the world’s tea trees, along with porcelain and silk, giving it significant economic power as tea drinking spread globally. The expansion of tea’s popularity accelerated in the early 1600s when Dutch traders brought tea to Europe in large quantities. Queen Catherine of Braganza, a Portuguese noblewoman, is often credited with popularizing tea among the English aristocracy after her marriage to King Charles II in 1661.

Amidst its expansion of colonial influence and rise as the new dominant world power, Great Britain saw a growing interest in tea worldwide. By 1700, tea in Europe cost ten times more than coffee, yet the plant was still exclusively cultivated in China. The tea trade became immensely profitable, leading to the creation of the clipper ship, the world’s fastest sailboat, driven by fierce competition among Western trading companies eager to deliver their tea to Europe first and maximize profits.

Initially, Britain paid for Chinese tea with silver, but as costs soared, they proposed trading tea for another commodity: opium. Opium is a highly addictive narcotic drug derived from the dried latex obtained from the opium poppy (Papaver someniferum). This sparked a public health crisis in China as addiction to the drug spread. In 1839, a Chinese official ordered the destruction of massive British opium shipments in protest against Britain’s influence. This act triggered the First Opium War between the two nations, resulting in intense fighting along the Chinese coast until 1842, when the weakened Qing Dynasty conceded the port of Hong Kong to the British and resumed trade on unfavorable terms. The conflict significantly diminished China’s global stature for over a century.

Seeking to further control the market, the British East India Company endeavored to cultivate tea themselves. They tasked botanist Robert Fortune with stealing tea from China in a clandestine operation. Disguised, Fortune embarked on a perilous journey through China’s mountainous tea regions, smuggling tea trees and experienced workers into Darjeeling, India. This clandestine endeavor further propelled the spread of tea as an everyday commodity.

Today tea is the second most consumed beverage in the world after water, and from sugary Turkish Rize tea, to salty Tibetan butter tea, there almost as many ways of preparing the beverage as there are culture on the globe.