Bread is the most widely consumed food in the world. It serves as a convenient and time-saving option for breakfast. But how much do we really know about the origin of bread? Behind the process of making bread lies a lovely traditional story. In today’s blog, we are going to explore some fascinating facts about bread.

Fundamental of Bread

Let’s start with the basics: what exactly is bread? Basically, bread is made from four main ingredients. First, there’s flour, which can be whole wheat or refined. Second, we need water to mix with the flour and make dough, just like when we make flatbread or rotis in the Indian subcontinent. Third, we add salt, and fourth, yeast.

You might wonder why we put salt in bread. There are three main reasons. Firstly, salt acts as a natural antioxidant, helping to preserve the bread so it lasts longer. Secondly, it improves the taste of the bread. And thirdly, salt strengthens the gluten in the dough. Gluten is what holds the bread together, and kneading the dough helps the gluten strands stick together. Adding salt makes these strands even stronger.

Now onto the yeast, which is a tiny single-celled organism belonging to the fungi group. When yeast reacts with the carbohydrates in the flour, it releases two components: ethanol and carbon dioxide. This reaction is called fermentation. The carbon dioxide bubbles produced during fermentation get trapped in the gluten, causing the bread to rise.

You may have noticed round and oval bubbles in bread. These are formed by the carbon dioxide released during fermentation. Alongside carbon dioxide, ethanol, which is alcohol, is also released. But don’t worry—when we bake the fermented dough in the oven, the ethanol evaporates, helping the bread rise even more. However, some alcohol remains trapped in the bread, though in small amounts. Research from the American Chemical Society in the 1920s found that bread may contain between 0.04% to 1.9% alcohol, but this tiny amount won’t harm you. In fact, it enhances the bread’s flavor.

This traditional method of making bread has been used by humans for centuries all over the world.

Flat bread vs Bread

In 1857, Louis Pasteur figured out how fermentation works, which helped us understand the process better. Before that, people were using fermentation without really knowing what was going on. When we make rotis, we don’t add yeast or salt, unlike when making bread. That’s why rotis stay flat and don’t puff up like bread does. Also, rotis don’t last long because they don’t have yeast or salt to help preserve them. Flatbreads, like rotis, are popular all over the world. For example, in Mexico, they have tortillas, which are similar to rotis. Tortillas are often made from corn, while rotis are made from wheat. You can find lots of different kinds of flatbreads in Southeast Asia and Africa too.

But, who came up with the idea to put in the normal flatbreads to put yeast in the normal flatbreads to make it expand?

Discover

Bread has been around for a really long time, going back thousands of years to when ancient civilizations started farming. People think bread-making began around 10,000 BC when folks started settling down and growing grains like wheat, barley, and millet. They figured out that if they ground up the grains into flour, mixed it with water, and baked it, they got bread, which was tasty and filled them up.

Historians argue about where exactly bread came from, but it seems like lots of different cultures discovered it on their own. The ancient Egyptians are often said to have made some of the earliest kinds of bread. They used wild yeast from the air to make their dough rise and become fluffy. Legend has it that one day, a baker in Egypt accidentally left his dough out for a while, and it puffed up when he baked it.

People loved the softer texture, so they started trying to make it happen again. But relying on wild yeast in the air was tricky because it wasn’t always there. Then, someone smart figured out they could use a bit of old dough with yeast in it to help new dough rise. That’s how humans slowly figured out how to make bread the way we do today.

Tradition to Industry

Around 2,300 years ago, in 300 BC, during Ancient Rome, baking was held in high regard as an art form and a respectable profession. Wheat was imported from African regions such as present-day Algeria, Tunisia, and Egypt to Rome for bread production. It’s believed that Christopher Columbus was the first to introduce bread to America. By the 1800s, bread had become a ubiquitous homemade staple in cultures worldwide, with baking considered an esteemed profession, even intersecting with art, religion, and spirituality.

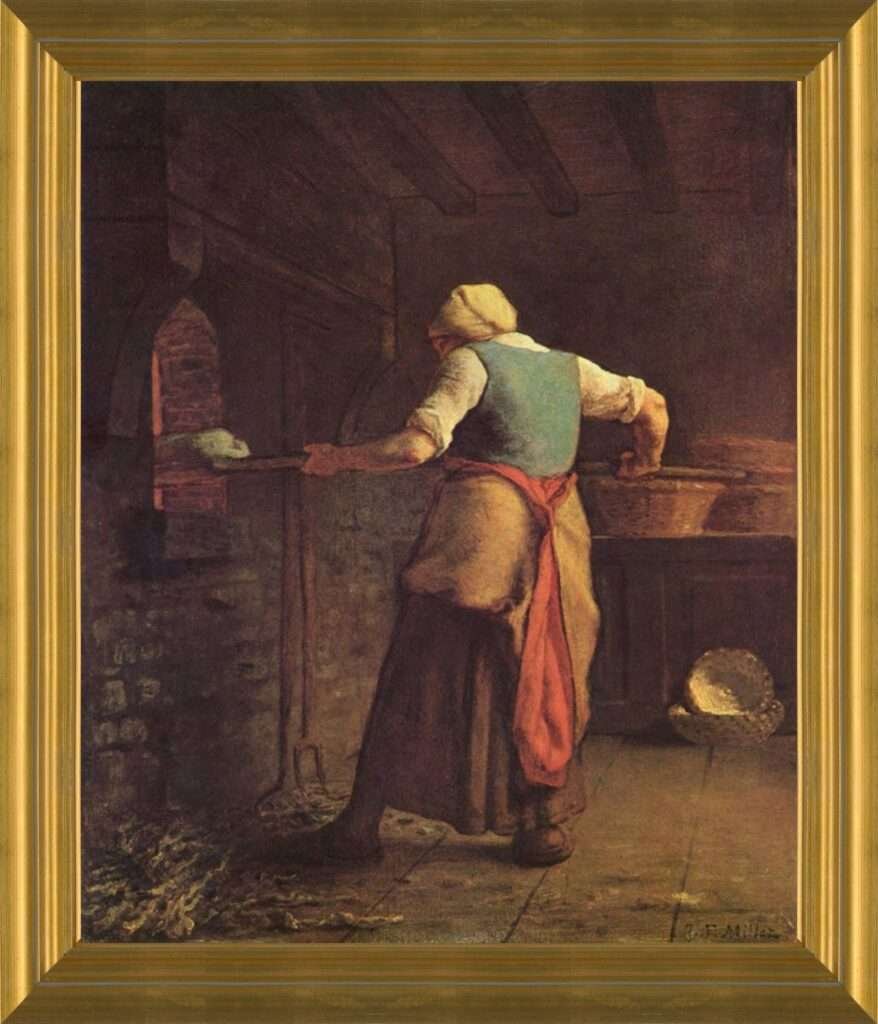

Look at the Jean-Francois Millet’s famous painting of a woman baking bread at home.

However, with the onset of the industrial revolution, the artisanal craft of bread-making transformed into an industry. Commercialization began, notably with the introduction of pressed yeast around 1867, attributed to Viennese bakers. This marked the transition from reliance on wild yeast to controlled yeast use, known today as Baker’s Yeast, available in convenient packets. Subsequently, the need for yeast led to the development of leavening agents like sodium bicarbonate, or baking soda. This substance reacts with acids present in ingredients like milk or buttermilk, or added lemon juice, releasing carbon dioxide to aid dough expansion. The innovation of moisture-free packets containing baking soda and acidic substances facilitated its use, eventually evolving into baking powder by the 1850s, further revolutionizing bread-making. In 1873, Edwin Lacroix’s improvement of the Swiss Steel Roller facilitated the efficient separation of wheat parts, streamlining refined flour production.

In conclusion, bread-making has evolved from a simple artisanal practice to a sophisticated industry, shaped by centuries of innovation and technological advancements. Yet, amidst these changes, bread remains a symbol of sustenance, culture, and tradition, connecting communities worldwide through its timeless appeal.